Polyconsole: This is how I make games now

Sunday, August 12th, 2012About a year ago, Ivan Safrin released his personal game engine under the name Polycode. I was impressed enough I began adopting the engine for all my personal game projects. However, a year after the release, it’s clear to me that although Polycode is a promising, powerful engine, it’s very hard to get started with. In hopes of doing something about this, I’ve got my own variant of the Polycode tools, which I would like to share with you. Using the tools below in place of the official Polycode distribution hopefully will make it easier to get started; make it easier to integrate Lua and C++ in a single game; and give you a much more up-to-date copy of Polycode than the (fairly out of date) one on the official website.

Below are three options– depending on exactly how dirty you want your hands to get– for using Polyconsole (my toolset). Each option includes support for Mac, Windows and Linux game development (although with options 2 and 3, there are currently complications for Windows users).

- What’s this now?

- Option 1: I don’t know what “compiling” is, I just want to make games

- Option 2: I want to combine C++ and Lua in a single game

- Option 3: I want to do everything myself

- TODOs and alternatives

What’s this now?

Polycode is a general game engine with support for C++ and Lua. It supports a broad range of features out of the box, including pixel shaders, 2D and 3D physics via Box2D and Bullet, and the standard niceties like resource management and xml serialization. Support for networking, mobile devices, and a Stencyl-like IDE are being worked on and hopefully will be eventually added.

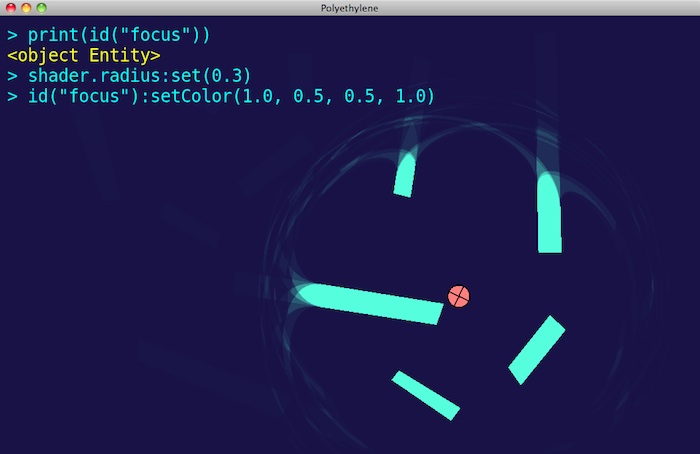

Polyconsole is my personal toolset for using Polycode– technically Polyconsole is an alternative to the “Polycode Player”, which is the official way to write Lua programs with Polycode. Polyconsole basically just loads a game written in Lua and runs it, along with a realtime Lua console for testing stuff out while you play:

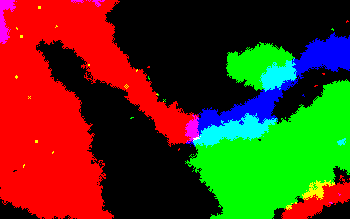

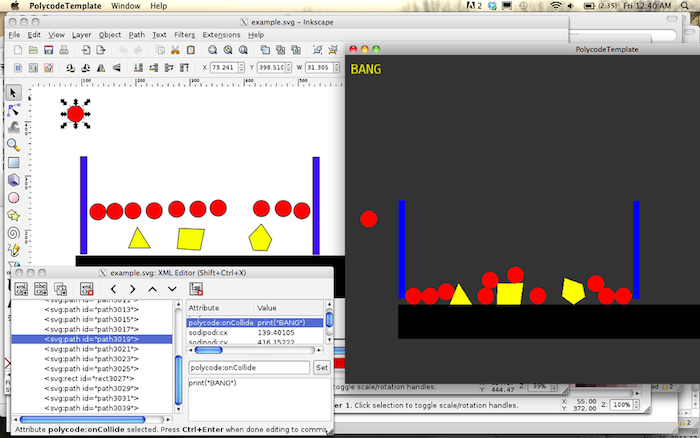

If you run your game in Polyconsole you’ll also have access to some utilities I added that aren’t in standard Polycode, like a 2D scene loader for SVG files which you can make in Inkscape:

Here completely within Inkscape I’ve drawn a little 2D physics scene, set weights and such for the various objects, and in the case of the one red ball at the top I added a Lua collision handler (it prints “Bang!”). On the right you can see the aftermath where Polyconsole has loaded all this up.

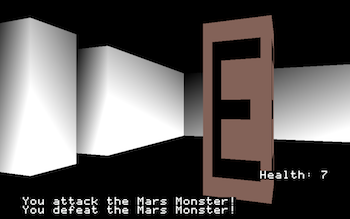

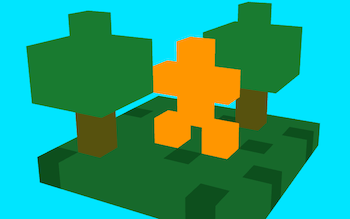

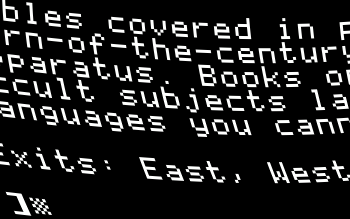

These are simple examples, but I’ve used this basic framework to make some complex and varied things very rapidly. Here’s some stuff I’ve made with Polycode and Polyconsole this year:

So, how does one use this?

Option 1: I don’t know what “compiling” is, I just want to make games

Below you can download prebuilt versions of Polyconsole for Mac, Windows and Linux, and just start writing games with Lua:

How to use this

Polyconsole loads the game it’s running out of a file named “media.pak” (actually a zip file) in its internal resources. It has a mod system though, whereby if it sees a file named “mod.zip” or a directory named “mod” in the same directory with it, it will selectively replace the files in media.pak with the “mod” files.

The version of Polyconsole above is set up so you can just write a whole game in the “mod” directory. In this package, the “mod” directory is preloaded with the contents of the sample program in media.pak. The package also has two extra magic files set up for you: “settings.xml” and “debug.xml”. The settings.xml lets you set the size of the window Polyconsole runs in. (Without this file, the game will just run full screen.) The debug.xml on the other hand, just by being there, causes Polyconsole to run in debug mode. This means you can access the Lua console, by hitting tab and then typing (you can hit tab again to hide it). Also in debug mode if you hit “esc”, all the current scripts, textures, images etc will be reloaded immediately from disk.

If you open up the mod/media directory included along with this Polyconsole, you’ll find the following:

init.txt: This describes the initial “room” that Polyconsole loads.

example.svg: This is the little sample physics scene in the demo.

material/: This directory contains textures and shaders, and the basic.mat xml file that describes them.

overlay/: This directory contains all your Lua.

Games in Polyconsole are made up of what I call “overlays” and “rooms”. An “overlay” is just a little package of Lua code– it contains one Lua script to run when the overlay loads, one Lua script to run when the overlay is closed, and one Lua script that runs once per frame as long as the overlay is up. A “room” on the other hand is a list of overlays and SVG files which Polyconsole loads all in a bunch. So for example in an average game I might have one room for the title screen, one room for the game over screen, and one room for the game itself. Alternately I could make each level its own room, if that makes more sense for the game. The sample Polyconsole program linked above contains only one room, which (as you can see if you look in init.txt) loads an overlay named “game” containing the code for the demo, the example.svg that describes the 2D scene, and standard “startup” and “shutdown” overlays. (You’ll always want to make the standard startup overlay the first thing in a room spec and the shutdown overlay the last thing in a room spec, because these are used by Polyconsole’s memory management.)

So to very quickly get started with Polyconsole you can download one of the above packages; open the exe; and while it’s running, open the mod/media/overlay/game folder and edit the onLoad and onUpdate scripts included within. Then whenever you change a line, you can go back to the program and hit “esc” to see your changes. (If it didn’t work, you can hit “tab” to see the console, where any errors will be printed.)

If you want to know how to write Polyconsole code, the following documentation should be helpful:

There’s also a rudimentary help system built into Polyconsole if you type help() at the console prompt.

You can find examples of Polyconsole code by looking at any of my games since “Markov Space”, or skimming of my in-development games I haven’t finished yet. They’re all built with this framework, and they all come with source code (and even if they weren’t, you could pull out the lua source just by pulling out the media.pak and unzipping it). Some of these are under no-commercial-use licenses, but if there’s something you want to copy out of one of my games just let me know and I can relicense it.

When you’re done

If you decide to write a game as a mod folder, once you’ve completed your game you can do the following to make something releaseable:

- Zip up the mod folder into a “mod.zip” file, and remove the “mod” folder itself

- Remove the settings.xml and debug.xml files

- Change the names in the Readme

- Rename “Polyethylene” to something not stupid

And you’ve got a game! You can then port your game to [Mac, Windows, Linux] by downloading one of the other two packages above that you didn’t install, and dropping the mod.zip in.

Option 2: I want to combine C++ and Lua in a single program

Writing these Lua mods will only get you so far, though. To me the entire appeal of Polycode in the first place is that I could write a game in Lua, getting the ease of use of something like Flashpunk– but if I really *needed* the power of C++, I could write C++ extensions that did whatever strange thing I wanted. I’m not restricted by what the developers of the VM or the browser plugin or whatever thought to put in, because Polyconsole is the Lua “VM” effectively and I control that. If you want to do this too, you’ll need to compile your own copy of Polyconsole.

To make that easier, here’s the source code to Polyconsole, packaged in each case with a complete build of the Polycode library. (The source is identical between the three versions, the difference between the three versions is which version of Polycode is included.)

- Mac version

- Windows version (with complications)

- Linux version

With complications? Wait, what’s that about? Well, there’s a problem with the Windows version right now. Most people writing C++ software for Windows use Microsoft Visual Studio. But I don’t have a copy of Windows, so I don’t use Visual Studio. Instead, I use MinGW, which is an open source compiler that makes Windows exes and can be run on any operating system you like.

But: It turns out that if you have a library built with MinGW, it can’t be used with Visual Studio, or vice versa. Worse, not only are MinGW and Visual Studio incompatible, but each individual version of MinGW is incompatible with every other! So, the Windows Polycode I have linked above was made with MinGW32 version 4.3.0. That means you can only compile that version of Polyconsole with MinGW32 4.3.0– nothing else. (The actual, final .exe games made with this system will run on any Windows machine.)

So I’ve got a list of instructions I wrote up for how to install MinGW, MSYS and Python so you can compile Polyconsole on Windows, but when I got someone to test them, they didn’t work– because you can’t get an installer for MinGW32 4.3.0 on Windows anymore, and the versions accessible with their snazzy new mingw-get system aren’t compatible with 4.3.0. I’m working very hard on trying to find a solution for this– I need to either get a modern version of MinGW32 that runs on Mac or Linux, or I need to get an installer of MinGW32 4.3.0 for Windows I can give you, or I need to get a copy of Windows so I can just build the darn thing with MSVC. When I’ve figured out a solution, I’ll come back here and post it– any suggestions you might have are welcome. But I don’t have a solution yet. Sorry.

In the meantime, hilariously, you can build a Windows version of Polyconsole with the Windows package linked above– if you have a Macintosh. You just have to run the MinGW-for-Mac installer linked here. (This is what I do with my own games.)

How to use this

The first and most important thing I can tell you is use version control. Take that whole package you just downloaded and add all the files to a hg or git repository. Otherwise, the game bits you wrote will get all mixed in with the Polyconsole code, and it will be really, really hard to remember what you changed or upgrade to a different version of Polyconsole if you want to do that later. If you don’t know how to use hg or git, on Windows you can make this really really easy by downloading the Tortoise programs. On Mac or Linux, you can just go to the Polyconsole directory in the Terminal and run: hg init .; hg add .; hg commit -m "Initial"

With that out of the way, assuming you can even install the appropriate compiler, the rest is pretty easy. If you’re on a mac, open PolycodeTemplate.xcodeproj and build and run. If you’re in the Windows version, navigate to package/win and run make. If you’re in the Linux version, navigate to package/lin and run make.

The one other thing you do need to know is how to add C++ functions that are callable from Lua. When you build Polyconsole, it will run a script that’s part of Polycode called create_lua_library that will suck out parts of your program and make them visible to Lua. You need to tell it which parts of the program are supposed to be Lua-visible. To do this, you need to edit the file lua_visible.txt in the base of the repository to add the names of every header file you want the script to look in, and also edit media/project_classes.txt to add the names of any classes you want Lua to be able to use. You don’t want to just add all your header files to lua_visible.txt, by the way, because create_lua_library can sometimes get confused if you try to feed it overly fancy stuff.

Mostly, I don’t mess with that and I just add methods to the one class that’s already set up in there to be visible to lua– “project_bridge”. This is found in source/bridge.cpp and source/bridge.h; at startup, Polyconsole sets up an object of type project_bridge visible to Lua under the name “bridge”. So you can just add a new method void arglebarf() {} to bridge.h, recompile, and suddenly Lua code will be able to call bridge:arglebarf().

When you’re done

The makefiles attached to these packages make complete finished versions of Polyconsole, so there you’re pretty much done. On mac though you’ll want to run ./package/pkg_mac.sh from the project root to make a “Release” version with a readme and pretty stuff.

You also might want, before you compile, to run this magical perl oneliner which will rename the sample program from “Polyethylene” to something more sensible:

perl -p -i -e 's/Polyethylene/YourGameNameHere/g' * */* */*/* */*/*/* */*/*/*/*

Option 3: I want to do everything myself

What I originally intended with Polyconsole was that instead of writing a mod to this “Polyethylene” example program, or having to download a whole compiled version of Polycode from me, was that Polyconsole should just download and compile Polycode for you for all the different operating systems you want to support. You can still get this, if you download Polyconsole from the Bitbucket page.

There’s rather a lot of documentation at the Bitbucket page explaining how this works, but basically, I wrote a little program called manage.py that automates building Polycode; and makes it easy to make your own modifications to Polycode by keeping a binary cache of Polycode versions you’ve previously built, and keeping track of which Polycode version goes with which SCM checkin. Unfortunately, in practice the script wasn’t nearly as easy to use as I’d hoped, and when people tried to run it on their own computers unexpected things went wrong. (Also, it doesn’t work at all on Windows right now, although I think someday it will.) So unless you think you’re willing to tinker a bit and debug CMake problems if something goes wrong, you might be better off downloading one of the Option 2 packages above.

TODOs and alternatives

So: This is still all in progress. This is all a little jumbled. I’ll be continuing to make improvements to this. Here are the things at the top of my To Do list:

- I need better Windows support.

- This should all be documented more cleanly than it is.

- Rooms should be able to include 3D physics scenes– not just 2D ones.

- A lot of little features and cleanup are needed. Right now Polycode programs crash when you run them on a computer with an OpenGL 1.x video card; these should be supported, or at give you a polite error message. There should be an onClick handler for overlays. I think vsync is broken on Windows. There should be an option to use PortAudio for sound or at least do realtime-generated sound with OpenAL. And so on.

If you’re interested in helping push along Polycode development yourself, Polycode’s github page is here (my fork is the one marked “mcclure”) and as linked above I have a BitBucket project for Polyconsole here.

My goal here is to make something people can actually sit down with and use for development. So if you feel what’s linked above isn’t enough to be a usable development starting point in your view, feel free to post below and let me know what you think is missing.

In the meanwhile, you also may want to be aware of these alternatives to Polycode:

- Gameplay3D— Haven’t used this but this is something RIM released, it seems to have many of the same features as Polycode including Lua scripting support and it supports mobile.

- Panda3D— Haven’t used this either, again offers about the same features as Polycode, seems a lot more heavyweight than either Polycode or Gameplay3D but also very complete.

- Unity3D— This is the gold standard in this kind of engine right now, and unlike Gameplay3D or Panda3D I’ve actually seen indie games using it. It is a little larger in scale, it comes with a VM so that you can run code written in C# or Javascript in it and it has a fancy IDE with a built in scene and 3D model editor. However, unlike everything else on this page, it is closed source and costs MONEY.

- Love— This is a 2D-only, Lua-only game engine. I’ve heard really good things about it, and it will definitely be simpler than Polycode.

- Jumpcore— This doesn’t much resemble the other items on this list, I link it only because I made it. This was what I used to make games before Polycode. It’s a really stripped-down, C++-only library that’s really more just a wrapper for porting SDL games to iPhone/Android, but if you are looking for a simple C++ starting point this might be useful for you.

- Flashpunk and Flixel— These are some great 2D gaming Flash libraries. They offer programming interfaces like Polycode’s, but they’re really mature and have really strong communities. Since they’re Flash, you’re limited to what Flash can do and where Flash can run, but that’s increasingly “everything” and “everywhere”. I’ve got some brief experience with FlashPunk and liked it.

- Pixie— Also a little different from the other listed items, but: These guys wrote a Stencyl-style editor for HTML5 games, in HTML5, so you can make a tiny game on their website and upload it right there. It seems really cool.

That’s all I’ve got